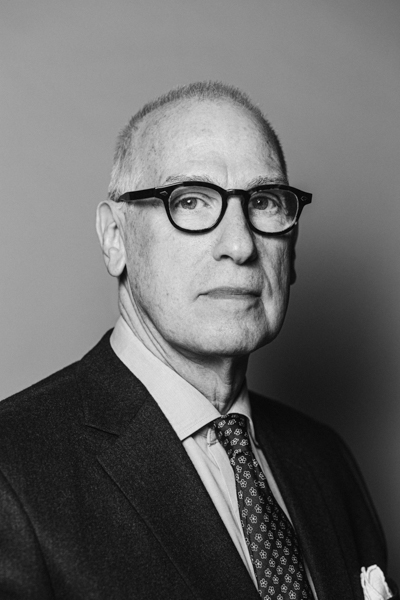

It would never occur to Scott Baskin, even on the other side of a thirty-five-year career as an executive, to step away from the business world.

While he’s certainly earned the right to take it easy after serving for more than three decades in leadership roles for menswear retailer Mark Shale—a family company founded by his grandfather—Baskin spends much of his time working with other small business owners in the hope that they can glean some of his hard-won wisdom and find success in a challenging market.

“At this point in my life, with my gray hair, I love all kinds of different businesses, and mentoring is one way that keeps me involved in learning about different businesses,” Baskin says. “It’s intellectually stimulating. One of the most enjoyable parts for me is working with a business that is very different from mine, because in lots of ways, I think I provide better value—you ask more questions and dig deeper when you aren’t familiar with the business. It’s that genuine curiosity, he says, paired with a deep understanding of how small businesses work generally, that can be the most helpful to entrepreneurs.”

Baskin began his career as an attorney, first working for a stint at the US Attorney’s office in Chicago, where he was involved in “a couple of fascinating mob prosecutions,” he says with a laugh.

Afterwards, he spent almost four years on the Capitol Hill staff of US Representative Abner Mikva of Illinois and working as a legislative assistant on the House Ways and Means Committee. Soon, though, the pull of the family business brought him to Mark Shale, where he spent the rest of his career.

“It’s the kind of business that mixes the creative with the analytic and all kinds of things, which is fun,” Baskin says. “Every day had a new challenge, which I liked a lot.”

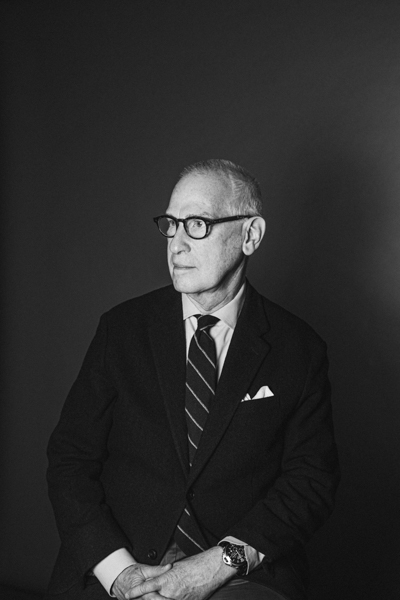

Now that he’s retired, Baskin devotes his time to mentorship and board service, but he emphasizes that he didn’t suddenly decide to start advising other entrepreneurs after he retired—it grew organically as others came to him for advice, and it developed because he has always been open to those conversations and relationships.

“It started with a friend who had a business problem and said, ‘Do you have ten minutes? Can I share a problem?’ Over the years, there have been a lot of friends who knew I was in business and would call and say, ‘Hey, I have a friend who has this business. He’s got an issue. Could you talk to him?’” Baskin says. “And that led to, depending on the nature of the problem and the needs of the business, sometimes a longer-term relationship, sometimes just a cup of coffee. You just don’t know.”

Over the past twelve years, Baskin has joined more formal mentorship matching programs: he’s part of the Young Presidents Organization (YPO), which has a formal mentorship program through EO, the Entrepreneurs’ Organization. He ran the program for three years as chair, matching people with the right mentors, recruiting mentors and mentees to join, and running the programming. He also sits on the board of the Small Business Advocacy Council, a nonpartisan, nonprofit organization that advocates for small-business interests in the political arena. He currently serves as the unpaid CEO.

“We have members that go from the far right to the far left of the political spectrum, but we all get together and focus on problems and how to solve them,” Baskin says. “When you do that, the partisan stuff disappears, which is fascinating.”

Membership in these types of organizations can help both those looking for guidance and those hoping to help fellow small-business owners, but Baskin says that no matter how you find a mentor or mentee, the most important first step is to listen. He advises mentors to begin by asking a lot of questions about a person’s particular business and its challenges.

“The other part is trying to get an understanding of their financials,” Baskin says. “Financial reports are less like a report card and more to be used as a road map to try to set goals and give direction to the business.”

Small business owners and executives are often so focused on the day-to-day challenges of a business—and Baskin counts himself among those who have made this mistake—that they don’t take the time to sit down and look at their financials.

“If you’re the owner, you’re in the trees. You don’t see the forest, and you don’t pay a whole lot of attention to the financials, the business, because you’re just busy putting out fires and you’re busy doing the urgent, not the important,” Baskin says. “So a big help is having someone, a board member or sometimes just an advisor from the outside, who sits down and says, ‘Let’s spend fifteen minutes going over last month’s financials.’ Everything there is a question. ‘Why were sales good? Why were sales bad? Why was this expense high? Why was this expense low?’”

Asking those questions enables the entrepreneur to take a wider view of their business and talk through some of the high-level problem solving and planning that’s crucial for longevity and profitability.

Of course, asking the right questions at the right time is a skill that Baskin has cultivated over many years of gaining insights into how different businesses succeed—as well as how they stumble. “I tell all the people I mentor: there are few mistakes I haven’t made in business, and I want someone to reap the benefits of these mistakes.”