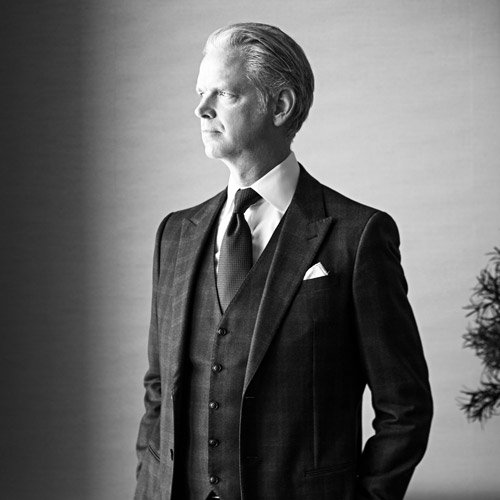

While some financial leaders fear the unknown, Bob Barron thrives on uncertainty. In many ways, he has no choice. As a chief financial officer in the entertainment industry, a measure of ambiguity comes with the territory. Barron came to Twentieth Century Fox Television (TCFTV) in 1994 as senior vice president of finance and eventually assumed the top financial post for the studio in 1999. He also oversees finance for the domestic television sales and consumer products divisions.

His department assumes traditional finance and accounting responsibilities—but Barron’s team must execute in a creative environment to support diverse television productions; partner with vastly different domestic and international distribution partners to monetize content; and navigate an ever-changing and disjointed digital world to get content into the hands of consumers.

These issues come together once a year during pilot season, when companies like Fox produce single episodes of a series they hope to sell to a network. Barron and his team work with production executives to estimate the production costs without knowing exact details. They have to build in enough latitude to allow the show’s directors and producers to get creative and entice a buyer to order more episodes.

But it’s a balancing act. “A pilot is an investment. We need to make the best show possible, but we also have to produce each show as efficiently and as cost effectively as we can,” Barron explains. Factors like visual effects, music rights, casting, and location all determine costs.

With the budget set, a pilot moves into production. While Barron says he leaves casting, scriptwriting, and other key creative decisions to “the professionals,” he understands their world. “This is a unique industry, and financial people in entertainment have to stay flexible,” he explains. “Making TV shows isn’t a science, it’s an art. CFOs have to give room and understand that each production is unique, and each show has its own needs that don’t really exist in any other industry.”

To maximize the return on their investments, Barron’s team supports a roster of studio executives to build an eclectic programming portfolio. “We want to appeal to different viewers in different markets around the world,” he says, adding that teams at Fox consider long-term value to help determine a series’ production budget. Pilots that get a series order from a network may stay on the air for many years, and ratings are critical.

After launching on US platforms, shows that do well enough can succeed overseas and on other distribution platforms. However, sometimes shows that aren’t big hits in the United States still do well in other markets, and sometimes shows that enjoy domestic success don’t resonate in another culture. “There’s just no rule to what will work,” Barron says. “That’s why Fox believes in fresh, new, brave ideas. Mediocre TV is failed TV. We want to take risks. We want to be bold.”

To be bold, Barron and executives at Fox’s studios have to stay on top of seemingly constant changes in the industry. For Barron, it’s almost second nature. He was born and raised in Southern California with a father who was a certified public accountant and an executive at Paramount and Time Warner.

Barron completed undergraduate and MBA degrees before returning to his home state to take a job as a financial analyst at RCA Columbia Home Video when the format was just getting its start. He watched the home-video market explode and later became a senior vice president of TCFTV in 1994. Then, the fledgling company had just a few shows. A decade later, the studio was the top production company in Hollywood.

In his career, Barron has seen the introduction of DVD, the dramatic increase of demand for US content in international markets, Blu-ray, mobile, and other disruptors—and the industry continues to grow and evolve.“People are consuming our content in new ways. It’s now about when, where, and how they want it, and they’re getting it on any and every device,” Barron says. The new reality is forcing his teams to work with Fox distribution divisions to find new and better ways to deliver Fox content.

To find success and support the business, finance must understand the new requirements and expectations thrust upon the department. “There’s more and more interest in understanding exactly where we are financially, and where we’ll be in three to five years,” Barron says, adding that he gets more requests than ever before for profit and loss statements, balance sheets, and other key financial documents from the company’s

top brass.

While Barron’s work may seem difficult, he credits a long-term and loyal financial team with helping him navigate the fast waters of entertainment finance. He works to communicate well and make sure each member of his finance team understands what’s needed and how he or she can get the right information to the right place.

He also tries to lead by example. “This is an industry that you have to have a passion for. If you don’t love what you’re doing, you’re probably going to be mediocre at best,” Barron says. “I got into this industry because I enjoy it, and two decades later, I still love coming to work every day.”

When Barron started his career, TCFTV was a fairly modest studio operation that supplied programming to the Big Four networks (ABC, CBS, NBC, and Fox). Soon after, new cable channels started ordering original programming that opened the door to the studio as a content producer.

Now, outlets like Netflix, Hulu, and Amazon are hungry for original programming. While some would see the changes as a challenge, Barron sees only opportunity. “We’ve been given so many more places where we can sell our content,” he says. “The number of buyers has increased dramatically, and that’s great for business.”

With shows like Empire, The Simpsons, Homeland, Modern Family, The X-Files, and Family Guy, Fox is poised to continue its legacy of building some of TVs biggest hits.