The North Dakota State Water Commission (ND SWC) makes the subject of water management anything but dry. Consider how it handles one of our most valuable resources.

Like similar statewide organizations, ND SWC seeks to effectively manage water—the flow and stoppage. Still, it differentiates itself in substantial ways, most considerably in its organizational composition. “We’ve combined the water commission and the state-engineer office to create a unique entity,” says Lee Klapprodt, ND SWC’s director of planning and education, describing an arrangement uncommon to many states, where engineering and resource-related activities are typically divided as if by a levee.

Landlocked states need to approach things a bit differently. Consider North Dakota. In the United States, it ranks 19th in total area and owns all of its water—below the surface, on the surface, and above the surface. Here, the state engineer issues water rights to ensure the most beneficial usage, while the water commission focuses on water management and infrastructural development, which entails a broad spectrum of activity: construction of water-supply systems, provision of raw water to communities, and development of water systems that serve North Dakota’s rural regions, which are numerous. The state-engineer/water-commission interaction—both headed by Todd Sando—results in an extremely effective system that serves specific needs of the state’s entire population.

Landlocked states need to approach things a bit differently. Consider North Dakota. In the United States, it ranks 19th in total area and owns all of its water—below the surface, on the surface, and above the surface. Here, the state engineer issues water rights to ensure the most beneficial usage, while the water commission focuses on water management and infrastructural development, which entails a broad spectrum of activity: construction of water-supply systems, provision of raw water to communities, and development of water systems that serve North Dakota’s rural regions, which are numerous. The state-engineer/water-commission interaction—both headed by Todd Sando—results in an extremely effective system that serves specific needs of the state’s entire population.

This arrangement helps the Bismarck-headquartered organization accomplish its mission: to promote judicious water management and development. A forward-thinking

enterprise, ND SWC developed a vision wherein both current and future state residents can appreciate adequate, high-quality water supply, enjoying a resource that promotes both health and economic growth—even though it can sometimes be overabundant (flooding) or nowhere to be seen (drought), as Klapprodt relates.

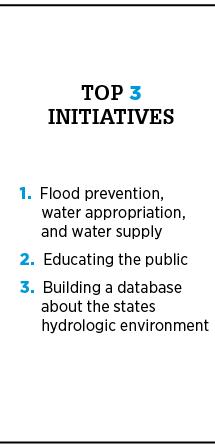

Right now, overabundance—too much water flowing into a little space—is a primary concern, which prompts flood-control projects through collaboration with contractors and partnerships with local entities. Such relationships result in construction of dams, levees, and drainage systems. Klapprodt describes the climatic conditions that moved the organization in this direction, saying, “North Dakota has faced a severe wet cycle that created recent flooding in many parts of the state. We address flood issues with prescribed processes that enable us to deal with them as they occur.”

As such, ND SWC has turned its eyes, and flood-preventive measures, toward several areas in the state. In the Red River Valley, it is involved in a water-diversion project, in a region long beset with water-related catastrophes. In the Devils Lake Basin, flooding began in 1993 and, as Klapprodt reports, the ongoing situation—which has destroyed homes and businesses and has compromised farmlands—reached record-setting levels and advanced to the “hypercritical” stage. “We’re working with communities to resolve the recurring Devil’s Lake problems,” Klapprodt says, referring to the appropriately named 3,810-square-mile Red River sub-basin.

State, local, and federal governments are responding in various ways to mitigate Devils Lake flooding problems. The State of North Dakota and US government have directed about $1 billion toward flood response efforts. Much of the money has goes toward moving roads, rail and power lines, water outlets, and levee construction.

To address flooding issues and other needs, the ND SWC will use the new dollars appropriated for the next biennium to fund collaboration between federal and local entities to develop projects across the state, Klapprodt says.

Still, Klapprodt must feel like the Dutch boy with not enough fingers to plug the dyke. He identifies areas where ND SWC focuses attention. “This year, serious flooding occurred along the Red River, Missouri River, and Souris River at a level, and in some cases, never before seen. So, right now, we’re in a too-much water cycle,” he says. “In the past, we’ve gone through cycles of too little water. Each cycle drives our activities—to get water from where it is to where it isn’t.”

This leveling effect isn’t easy. But North Dakotan residents can rest assured that its water commission is on the job. Don’t take that tap water for granted.